Tashi Laptsa

I'm back in Kathmandu after a successful ascent of Ama Dablam. More on that later. Here's the story of the four day journey from Rolwaling up and over Tashi Laptsa, one of the most challenging passes in the Himalaya, and down into the Khumbu. You know you're in the Himalayas when the passes are 19,000 ft!

Tsho Rolpa, a terminal lake, is one of many in the Himalayas prone to glacial outburst floods. One here in 1986 was very serious to my understanding, and increased glacial melting due to climate change is expected to make such flood events more frequent and severe in the future.

Tsho Rolpa, a terminal lake, is one of many in the Himalayas prone to glacial outburst floods. One here in 1986 was very serious to my understanding, and increased glacial melting due to climate change is expected to make such flood events more frequent and severe in the future. Babu Ram walks into Chukima camp, with Nachugo behind.

Babu Ram walks into Chukima camp, with Nachugo behind. Pika!

Pika!

Dust at the head of the Rolwaling valley is from a massive and active landslide

Dust at the head of the Rolwaling valley is from a massive and active landslide

Furtemba crosses active landslide on the way to our high camp below Tashi Laptsa. We kinda ran:

Furtemba crosses active landslide on the way to our high camp below Tashi Laptsa. We kinda ran:

One of the finest places I've spent a night:

One of the finest places I've spent a night:

Purna and Babu Ram ascend ever steepening glacial ice with outrageous loads:

Purna and Babu Ram ascend ever steepening glacial ice with outrageous loads: Furte borrowed my axe to chop steps for the porters

Furte borrowed my axe to chop steps for the porters We donned crampons for the final few hundred meters up Tashi Laptsa. I was glad to switch to mountain boots as my toes were violently cold.

We donned crampons for the final few hundred meters up Tashi Laptsa. I was glad to switch to mountain boots as my toes were violently cold. Descending Tashi Laptsa was tricky and arduous

Descending Tashi Laptsa was tricky and arduous Tengkangboche:

Tengkangboche: Descending some of the coolest glacial polish I've seen:

Descending some of the coolest glacial polish I've seen: Furte whipped up one of the best high altitude meals I've had. Super spicy potato curry with Tibetan fried bread:

Furte whipped up one of the best high altitude meals I've had. Super spicy potato curry with Tibetan fried bread: Babu Ram's basket was toast

Babu Ram's basket was toast

Coming into Thengbo was spectacular

Coming into Thengbo was spectacular First view of Ama Dablam, our next objective

First view of Ama Dablam, our next objective

Thame:

Thame:

The trails of the Khumbu are like highways!

The trails of the Khumbu are like highways! Namche Bazaar, the largest settlement in the Khumbu valley:

Namche Bazaar, the largest settlement in the Khumbu valley: Oh yeah, Mount Everest...

Oh yeah, Mount Everest...

Signs warn us of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF). I think it would help if the sign explained what the hell GLOFs are.

Signs warn us of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF). I think it would help if the sign explained what the hell GLOFs are.

Everest (behind) and Lhotse (R), the world's highest and 4th highest mountains. I made it about a thousand feet higher than the prominent Yellow Band without oxygen on Lhotse in 2013.

Everest (behind) and Lhotse (R), the world's highest and 4th highest mountains. I made it about a thousand feet higher than the prominent Yellow Band without oxygen on Lhotse in 2013. Pasang Tenzing, Furtemba and Leslie take a break on the way to Pangboche

Pasang Tenzing, Furtemba and Leslie take a break on the way to Pangboche Furtemba, brought to you by Ray Ban, Black Diamond, Mammut and Sportiva:

Furtemba, brought to you by Ray Ban, Black Diamond, Mammut and Sportiva:

Everest and Lhotse catch the last rays of sun from Pangboche

Everest and Lhotse catch the last rays of sun from Pangboche

Another privileged opportunity to meet with and receive blessings from Lama Geshe, the highest ranking Lama in the region. Once again he laughed at my "Nepali name"

Another privileged opportunity to meet with and receive blessings from Lama Geshe, the highest ranking Lama in the region. Once again he laughed at my "Nepali name"

Ama Dablam. Our route was the right hand skyline:

Ama Dablam. Our route was the right hand skyline:

Spinning the prayer wheels at Pangboche Monastery after our visit with Lama Geshe

Spinning the prayer wheels at Pangboche Monastery after our visit with Lama Geshe

Pasang walks to base camp

Pasang walks to base camp Ama Dablam base camp is so comfortable and beautiful. Nicest base camp ever!

Ama Dablam base camp is so comfortable and beautiful. Nicest base camp ever! Not to mention the outrageous comforts (welcome mat!) in our camp. Ascent Himalayas for the win!

Not to mention the outrageous comforts (welcome mat!) in our camp. Ascent Himalayas for the win! Tawoche from base camp:

Tawoche from base camp:

Resilience: A year and a half of recovery since the Great Earthquake

On April 25, 2015, Nepal was struck by a massive magnitude 7.8 earthquake. Some quick facts and figures : This event and subsequent aftershocks left over half a million households homeless, 1.4 million in need of immediate food assistance, and 5.6 million in need of immediate medical services. Nearly 9000 died and the economic cost was about $10 billion, roughly 50% of Nepal’s GDP.  Below, I survey the science behind this event, summarize the consequences, and take a more personal look at its ramifications in just one region, the Rolwaling Valley.Accumulation and Release Most who’ve been exposed to earth science concepts can tell you that the Himalayas are the product of a tectonic collision between the Indian Subcontinent and Asia. Far fewer, however, can describe how this process manifests. Earthquakes are the product of accumulated strain, or the deformation of rocks, which is then released suddenly. So in the case of the India-Asia collision, huge blocks of rock are deformed, storing elastic energy, which is then released suddenly through slip along a fault plane. The April 25 earthquake represented the release of a tremendous amount of energy along one of these main faults making up the structure of the Himalaya. It’s important to note that earthquakes aren’t like a bomb going off at a single point source, they occur along a plane which slips over a period of time. The point where the slip begins is called the focus…the point on the earth’s surface directly above the focus is called the epicenter.

Below, I survey the science behind this event, summarize the consequences, and take a more personal look at its ramifications in just one region, the Rolwaling Valley.Accumulation and Release Most who’ve been exposed to earth science concepts can tell you that the Himalayas are the product of a tectonic collision between the Indian Subcontinent and Asia. Far fewer, however, can describe how this process manifests. Earthquakes are the product of accumulated strain, or the deformation of rocks, which is then released suddenly. So in the case of the India-Asia collision, huge blocks of rock are deformed, storing elastic energy, which is then released suddenly through slip along a fault plane. The April 25 earthquake represented the release of a tremendous amount of energy along one of these main faults making up the structure of the Himalaya. It’s important to note that earthquakes aren’t like a bomb going off at a single point source, they occur along a plane which slips over a period of time. The point where the slip begins is called the focus…the point on the earth’s surface directly above the focus is called the epicenter. These concepts aren’t just important to scientists. Rather, they have real, life or death consequences for humans inhabiting earthquake prone areas. Let’s explore a few of the factors that shaped this event:

These concepts aren’t just important to scientists. Rather, they have real, life or death consequences for humans inhabiting earthquake prone areas. Let’s explore a few of the factors that shaped this event:

- Depth. Earthquakes always happen at depth. The shallower they are, the more you feel shaking on the surface. Makes sense right? This event had a focus of just 8 km, extremely shallow for an event of its size. Many earthquakes off the coast of Japan, for example, are 80 – 100 km or even deeper. The recent Haiti quake was 10 km.

- Direction of slip. Slip starts at a point, in this case in the Gorkha region about 77 km west of Kathmandu. But the slip propagated to the east. Thus, the regions most heavily hit were just to the east such as Sindhupalchok and Dolakha where over 95% of structures were destroyed.

- Rock type. It sounds counterintuitive, but the stronger the rock you’re on, the less the shaking. Unfortunately, in a country as mountainous as Nepal, the Kathmandu valley provides one of the few flat areas to build a large city. And flat areas surrounded by mountains are usually sedimentary basins, made of soft rock. Kathmandu itself is an ancient lake, so the shaking was amplified in this region…particularly heavily hit were historic buildings such as the Durbar Squares in Kathmandu, Patan and Baktipur…UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Date and time. Hey, it’s not all geology. The earthquake happened at noon on a Saturday. In other words, absolutely ideal timing for minimizing human suffering. In a country with many stacked rock or brick structures that are prone to collapse, the fact that people were out and about instead of sleeping, at work or in school was a huge factor. A night or weekday could have made this event ten times more devastating.

Long road to recovery in Rolwaling The Rolwaling Valley lies at the eastern end of Dolakha, just west of Solukhumbu, home to Mount Everest. People here are seminomadic (not sure if that’s a real term). A couple hundred inhabitants move up and down the valley with the seasons to tend to their farms and to let their livestock graze. In the photo essay below, I’ll show you a bit of my trip from Kathmandu to the end of the road and then the trek through Rolwaling. Heaviest hit was Simi Gaun, Furtemba’s home village, where he estimates over 95% of buildings collapsed. Some residents are still living in temporary housing (think: camping). People here are resilient, after all, they’ve been farming at over 15,000 feet for centuries, but they still need help. Everyone here has a story. I’ve been taken aback by how I’ve seen the houses of friends here like Angdu, Dawa Gyaljen, Mingma Gyalje destroyed. And our cook, Rajendra, showed me a huge scar on the center of his forehead, a tangible reminder of the massive icefall that killed 21 in Everest Base Camp.The rebuilding effort is inspiring. People have come from all over the country to help build a new monastery in Beding. But it’s a tremendous effort: everything in this valley has to be carried by people for three days to reach Beding from the end of the road at a cost of 80 rupees (80 cents) per kilo. So these tremendously important community buildings like schools, health posts, and monasteries represent an enormous economic cost of about $200,000. Ultimately, this adds up to a long road to recovery for the people of Nepal.The American Himalayan Foundation continues to take donations for earthquake relief.

Long road to recovery in Rolwaling The Rolwaling Valley lies at the eastern end of Dolakha, just west of Solukhumbu, home to Mount Everest. People here are seminomadic (not sure if that’s a real term). A couple hundred inhabitants move up and down the valley with the seasons to tend to their farms and to let their livestock graze. In the photo essay below, I’ll show you a bit of my trip from Kathmandu to the end of the road and then the trek through Rolwaling. Heaviest hit was Simi Gaun, Furtemba’s home village, where he estimates over 95% of buildings collapsed. Some residents are still living in temporary housing (think: camping). People here are resilient, after all, they’ve been farming at over 15,000 feet for centuries, but they still need help. Everyone here has a story. I’ve been taken aback by how I’ve seen the houses of friends here like Angdu, Dawa Gyaljen, Mingma Gyalje destroyed. And our cook, Rajendra, showed me a huge scar on the center of his forehead, a tangible reminder of the massive icefall that killed 21 in Everest Base Camp.The rebuilding effort is inspiring. People have come from all over the country to help build a new monastery in Beding. But it’s a tremendous effort: everything in this valley has to be carried by people for three days to reach Beding from the end of the road at a cost of 80 rupees (80 cents) per kilo. So these tremendously important community buildings like schools, health posts, and monasteries represent an enormous economic cost of about $200,000. Ultimately, this adds up to a long road to recovery for the people of Nepal.The American Himalayan Foundation continues to take donations for earthquake relief.

Alpine Exploration in the Ripimo Shar

Sometime earlier this year, I started taking a much closer look at the Rolwaling and which side valleys remained least explored. In particular, the Ripimo and Ripimo Shar (East) glaciers seemed like a gigantic hole, with few prior expeditions exploring their upper reaches. Those who did, the likes of Chris Bonington and Bruce Normand, reported giant peaks, natural beauty and wildness.A week ago, I set off from Na with what felt like a huge amount of support: Furtemba as the guide and climbing partner, Rajendra as cook, and three porters: Babu Ram, Purna and Buskar. It became clear pretty early on, however, that given the ruggedness of the upper reaches of the valley, that the resources we had were definitely not excessive. Our first day, we established camp at Omi Tso, a gorgeous alpine lake at the base of Nachugo and Omi Tso Go, one of the peaks for which I had a permit. The next day, we carried gear up the moraine and around the corner to an elevation of ~17,200 ft, where unfortunately, we discovered an astonishing lack of water on the upper reaches of the glacier. This meant a heartbreaking and super tricky descent down some of the tippiest talus I’ve ever encountered. Now that I’ve covered this stretch six times, I’d be happy to put the upper Ripimo Shar up against anything in a “World’s Sketchiest Talus” competition. It’s not an understatement that in certain stretches up to half a mile long, roughly 80% of the rocks (all of which ranged in size from volleyball to sofa) would suddenly shift. Often this would trigger a chain reaction. Heinous!

Sometime earlier this year, I started taking a much closer look at the Rolwaling and which side valleys remained least explored. In particular, the Ripimo and Ripimo Shar (East) glaciers seemed like a gigantic hole, with few prior expeditions exploring their upper reaches. Those who did, the likes of Chris Bonington and Bruce Normand, reported giant peaks, natural beauty and wildness.A week ago, I set off from Na with what felt like a huge amount of support: Furtemba as the guide and climbing partner, Rajendra as cook, and three porters: Babu Ram, Purna and Buskar. It became clear pretty early on, however, that given the ruggedness of the upper reaches of the valley, that the resources we had were definitely not excessive. Our first day, we established camp at Omi Tso, a gorgeous alpine lake at the base of Nachugo and Omi Tso Go, one of the peaks for which I had a permit. The next day, we carried gear up the moraine and around the corner to an elevation of ~17,200 ft, where unfortunately, we discovered an astonishing lack of water on the upper reaches of the glacier. This meant a heartbreaking and super tricky descent down some of the tippiest talus I’ve ever encountered. Now that I’ve covered this stretch six times, I’d be happy to put the upper Ripimo Shar up against anything in a “World’s Sketchiest Talus” competition. It’s not an understatement that in certain stretches up to half a mile long, roughly 80% of the rocks (all of which ranged in size from volleyball to sofa) would suddenly shift. Often this would trigger a chain reaction. Heinous! What started as easy moraine (above) turned to this...

What started as easy moraine (above) turned to this... We ended up having to do two carries to establish our base camp at ~16,500 ft. The next day, Furtemba and I established a route to ~18,500 ft on our main objective, unclimbed 20,856 ft Langdung. The highlight of the lower route (after a tremendous amount of talus of course!) was a few hundred meters of 4th and low 5th class sparkly granite. We soloed the whole section but did establish two rappels to make descent with heavy packs easier.

We ended up having to do two carries to establish our base camp at ~16,500 ft. The next day, Furtemba and I established a route to ~18,500 ft on our main objective, unclimbed 20,856 ft Langdung. The highlight of the lower route (after a tremendous amount of talus of course!) was a few hundred meters of 4th and low 5th class sparkly granite. We soloed the whole section but did establish two rappels to make descent with heavy packs easier. Classic butt shot. The rock was pretty good!

Classic butt shot. The rock was pretty good! Following a rest day, Furte and I returned to high camp on the summit push. We had a gorgeous bivy spot with spectacular views of the Ripimo Shar. Just after sunrise, we moved up on summit day, which involved a short glacier crossing, then ascent of a broad couloir and short traverse to the upper glacier. This was like entering a different world. A huge flat expanse extended to the Tibetan border, with the south face of Langdung, the highest objective around, towering over us on the right. We ascended this glacier to the base of the face, choosing a direct and fairly straightforward, if not monotonous, line up steep snow and alpine ice toward the summit. From the glacier, the face was ~600m (2000 ft). The face was in pretty good condition, allowing us to simul-solo nearly the entire route until it steepened to about 75 degrees for the last couple pitches. It was hard work, with little opportunity for rest or hydration. As we approached the last ridge, tantalizingly close to the true summit, things changed dramatically. Furtemba, usually steadily making upward progress, was now scraping his axes through horribly sketchy, unconsolidated snow in between bouts of profanity-laced outbursts. I took stock of my situation…one picket placed between us was the only thing keeping us on the mountain. After a lot of searching, Furte made an awkward move over a crevasse and onto the corniced ridge. I followed. It was there that we realized both how close and far we were from our objective. Probably 25 vertical meters and just 50-100 horizontal meters separated us from the snowcapped summit, yet the way was blocked by snow mushrooms on one side and overhanging, unconsolidated powder beneath the cornices on the other. Assuming this section were passable, we still had some mixed climbing of unknown difficulty to yet another cornice at the summit. It was just way too much risk for our liking. So I ascended the final couple meters of cornice and as I peeked my head over the edge I was met with thousands of meters of air down into Tibet. In the not-so-far distance, the world’s highest mountains stood before me: Cho Oyu, Everest, Lhotse and Makalu made up just a small part of the spectacular skyline.

Following a rest day, Furte and I returned to high camp on the summit push. We had a gorgeous bivy spot with spectacular views of the Ripimo Shar. Just after sunrise, we moved up on summit day, which involved a short glacier crossing, then ascent of a broad couloir and short traverse to the upper glacier. This was like entering a different world. A huge flat expanse extended to the Tibetan border, with the south face of Langdung, the highest objective around, towering over us on the right. We ascended this glacier to the base of the face, choosing a direct and fairly straightforward, if not monotonous, line up steep snow and alpine ice toward the summit. From the glacier, the face was ~600m (2000 ft). The face was in pretty good condition, allowing us to simul-solo nearly the entire route until it steepened to about 75 degrees for the last couple pitches. It was hard work, with little opportunity for rest or hydration. As we approached the last ridge, tantalizingly close to the true summit, things changed dramatically. Furtemba, usually steadily making upward progress, was now scraping his axes through horribly sketchy, unconsolidated snow in between bouts of profanity-laced outbursts. I took stock of my situation…one picket placed between us was the only thing keeping us on the mountain. After a lot of searching, Furte made an awkward move over a crevasse and onto the corniced ridge. I followed. It was there that we realized both how close and far we were from our objective. Probably 25 vertical meters and just 50-100 horizontal meters separated us from the snowcapped summit, yet the way was blocked by snow mushrooms on one side and overhanging, unconsolidated powder beneath the cornices on the other. Assuming this section were passable, we still had some mixed climbing of unknown difficulty to yet another cornice at the summit. It was just way too much risk for our liking. So I ascended the final couple meters of cornice and as I peeked my head over the edge I was met with thousands of meters of air down into Tibet. In the not-so-far distance, the world’s highest mountains stood before me: Cho Oyu, Everest, Lhotse and Makalu made up just a small part of the spectacular skyline.

Everest, Lhotse and Makalu framed by peaks of the Ripimo Shar

Everest, Lhotse and Makalu framed by peaks of the Ripimo Shar Langdung's true summit just 25 or so meters higherReturning to our measly picket, we backed it up with another, and Furte stood on them to add some additional psychological protection. I made the first of 8 or so rope-stretcher rappels off the face, mostly snow anchors but a few v-threads where we could find decent ice. The rest of the day was fairly uneventful…hard work into the frigid evening, but not the most tiring or epic descent I’ve made. A few hours later, after breaking down our high camp, we returned to the rocky Ripimo Shar. Soon, we spotted the headlamps of Purna and Buskar, who gave us some tea and juice and shouldered our heavy packs for the boulder-hop back to camp.

Langdung's true summit just 25 or so meters higherReturning to our measly picket, we backed it up with another, and Furte stood on them to add some additional psychological protection. I made the first of 8 or so rope-stretcher rappels off the face, mostly snow anchors but a few v-threads where we could find decent ice. The rest of the day was fairly uneventful…hard work into the frigid evening, but not the most tiring or epic descent I’ve made. A few hours later, after breaking down our high camp, we returned to the rocky Ripimo Shar. Soon, we spotted the headlamps of Purna and Buskar, who gave us some tea and juice and shouldered our heavy packs for the boulder-hop back to camp.

Nachugo and Omi Tso Go from high on Langdung. Jagat, Charikot and Kathmandu are out in the distance on the right.

Nachugo and Omi Tso Go from high on Langdung. Jagat, Charikot and Kathmandu are out in the distance on the right. Our last look at Langdung's south face

Our last look at Langdung's south face ________________________________________________________________________________Some more photos to tell the story:

________________________________________________________________________________Some more photos to tell the story:

Tidbits from the Trail

All we do is laugh our way up the trail. This is a sawmill by the way. Everything here has been carried up the valley by local people. The waterfall situation in Rolwaling is ourtrageous. I think by the end of this post, you'll agree.

The waterfall situation in Rolwaling is ourtrageous. I think by the end of this post, you'll agree. We came up through the jungle from the valley floor. We've got close to 18,000 vertical feet to go!

We came up through the jungle from the valley floor. We've got close to 18,000 vertical feet to go!

I think this is when Furtemba casually told me that people occasionally run into tigers here. Like actual tiger tigers.

I think this is when Furtemba casually told me that people occasionally run into tigers here. Like actual tiger tigers.

Furtemba's cousin's house is the close one. She cooked us the most amazing meal over a wood burning stove.

Furtemba's cousin's house is the close one. She cooked us the most amazing meal over a wood burning stove.

There are like people-sized holes in most of these bridges.

There are like people-sized holes in most of these bridges. Remote, holy and unclimbed: the incomparable Gauri Shankar (Tseringma if you're a Sherpa)

Remote, holy and unclimbed: the incomparable Gauri Shankar (Tseringma if you're a Sherpa)

So, so wobbly!

So, so wobbly! The view down the last three days of trekking

The view down the last three days of trekking Beding, the largest village in Rolwaling. People here move up and down the valley with the seasons.

Beding, the largest village in Rolwaling. People here move up and down the valley with the seasons. Tseringma...steep from this side too!

Tseringma...steep from this side too!

The entrance to Na, the highest settlement in Rolwaling at just under 14,000 ft.

The entrance to Na, the highest settlement in Rolwaling at just under 14,000 ft.

Na

Na

Yakyakyak

Yakyakyak Rajendra (orange jacket, our cook) and porters getting ready for a day of trekking

Rajendra (orange jacket, our cook) and porters getting ready for a day of trekking

hmix is back

It’s been a long time since I’ve posted, but that doesn’t mean I haven’t been busy. The past year has been a wild ride, filled with ups and downs in professional, climbing and personal life. I got an NSF grant to study the biggest storms in the American West. I attended a workshop in the Dolomites and topped the trip off with some mixed and alpine climbing in Chamonix. I built a lab and have three wonderful research assistants. I fell in love. And in March, I moved home to Virginia and took care of my mom until her death last month.So now I write with mixed emotions from my tent at 15,500 ft or so in a remote, seldom-explored side glacier of the Rolwaling Valley, Nepal. Rolwaling is exquisite. The natural beauty and changing landscape along the way was remarkable.You can follow my daily check-ins by clicking on the “Where’s Hari?” tab at the top right of the page. We’ll explore this valley and try up to two climbs over the next ten or so days. After that, we’ll head back down to Na, the last village below and embark on the next stage of the trip.Over the next few days, I’ll release some photo essays from different portions of the trip. Below is a taste of what it took to get into the mountains…Shiva looks over Coca Cola

Our axle (or something that sounded similarly awful!) broke on the way up. The guys were laughing while fixing it. Mingma, the government representative for Simi Gaun is beneath the broken part as the guys rock vigorously

Our axle (or something that sounded similarly awful!) broke on the way up. The guys were laughing while fixing it. Mingma, the government representative for Simi Gaun is beneath the broken part as the guys rock vigorously

The long, winding road to Charikot

The long, winding road to Charikot You see the best paint jobs in Asia

You see the best paint jobs in Asia

Hell yeah we drove through that waterfall!

Hell yeah we drove through that waterfall! The way down to Jagat from Simi Gaon. The zigzagging road is for the construction of the first major hydro project in Nepal. After a 12 hour drive from Kathmandu, we started in the dark up 2000 ft of stairs through terraced fields of millet.

The way down to Jagat from Simi Gaon. The zigzagging road is for the construction of the first major hydro project in Nepal. After a 12 hour drive from Kathmandu, we started in the dark up 2000 ft of stairs through terraced fields of millet. Danu's gorgeous new lodge in Simi Gaon. More on the people of SImi Gaon later.

Danu's gorgeous new lodge in Simi Gaon. More on the people of SImi Gaon later. Simi Gaun is Furtemba's home, so I think we had to have tea with just about everyone in the village!

Simi Gaun is Furtemba's home, so I think we had to have tea with just about everyone in the village!

Pobeda: Elusive and Unrepentant, Part 2

Day 1After breakfast, we took a slow and steady several hours to inspect each other’s gear, count GU packets, and weigh the pros and cons of couscous. After a few hours, in hot sunshine, we shouldered our monster packs and headed up the moraine. Soon, we traversed onto the ice of the Zvezdochka (Starry) Glacier. While beautiful, it was bright, hot, slushy and a maze of seracs and narrow river slots. Icy blue pools fed spectacular waterfalls. As we neared Camp 1, snow bridges became slushier and sketchier and we roped up. Just as we started to wonder where the Dutch tents would be, Bob led over a small rise and whooped out in joy…two beautiful tents were pitched in a broad, safe site just shy of camp one proper. We divvied up tasks and got to work re-anchoring tents and sorting gear. I fetched water from a nearby crevasse pond…we would use every trick in the book to save fuel.Day 2We wanted to get up through the serac band before sunrise, but when our alarm went of at 4 it was snowing and nasty out. We gladly took the extra hour or so of sleep before we brewed up, got dressed and marched up the glacier. Soon we could see an Iranian group working through the difficult sections above, and it was quite obvious why this portion of the route to Dikiy Pass was feared: a narrow and rotten gully was our only access to vertical/overhanging seracs fixed with lines. We romped up the gully as fast as we could, but the heat of the day was already softening things up and making the going tough. At the base of the seracs proper, Bob encountered a tricky overhang which took a few creative ideas and a ton of swearing to overcome. I ended up opting for my hands and knees on a dicey narrow ledge that we’d fixed with an additional ice screw. Just above, I popped through a snow bridge (protected by fixed line of course, but annoying nonetheless). The temperature was absurd. I’d say it felt like the upper 80s to 90s. All this with a monster pack and the inability to swap out 8000m boots for flip flops. After a mid day snack, I took the lead of the rope team as we entered the broad and gentle valley to Dikiy Pass. As we rounded a corner that gave our first views of camp 2 above, I saw a few climbers above moving slowly. Soon we reached two Iranians who were dealing with exhaustion. We didn’t feel much better and continued the last few meters to camp. A lone Russian wearing ski goggles and suffering from extraordinary sunburn plodded down at a snails pace. I stopped to say hi and learned that one climber had died on the summit ridge. No more details were exchanged as he continued to lumber down towards the glacier below. That evening, as we watched from our spectacular site we watched in awe as the entire Russian and Ukrainian contingents descended. They looked like hell. No fewer than twenty men, some collapsing every few meters slowly made their way down the ridge. It was an exodus. Soon, we were quite alone. The mountain felt different.Day 3We awoke to good conditions. The route to camp 3 looked beautiful and exciting, but once we wove out of camp 2 and got onto the lower buttress, things became challenging in hurry. The snow was deep and soft, and the hordes of climbers who had descended the previous day had turned the bootrack into sloppy ruts. The going got rougher when the wind and snow began to pick up. I donned my outerwear and our team regrouped to rope up at a small crevasse. Just a few meters later, things really deteriorated. In horizontal snow, we yelled over the wind for a bit before deciding to chop a platform and make camp. With the three of us working together, we stomped and shoveled a generous site, set up the tent and jumped in.___________________________________________________________________________I felt a punch to my chest and lurched upright in the darkness. Bob was trying to wake me but I was already beyond alert. The roar of the wind started so suddenly, Bob had thought an avalanche was barreling down on us and was bracing for impact. So much for the weather. We spent the next five or so hours til dawn getting hammered by wind and spindrift out of the west so violent that it filled our vestibule with snow and was starting to crush us. Periodically I sat up to punch the consolidating snow to clear some space for sleeping. By the time the morning came, we knew we were pinned down for the day. Bob, always a team player, got out and started shoveling first. Our tent had been buried to the brim on the uphill side and our guy lines were coated in rime ice. We learned that those above us at 6400m had an ordeal in the night but were okay.Day 4Later in the morning, things cleared in a most spectacular fashion. Below, a sea of snowcapped peaks stretched in all directions. The magic of the Central Tien Shan was alive. All of our stuff luckily got dry and we spent the day resting and discussing the weather. What would we do? Later in the afternoon the winds picked up. Soon, we heard shouting voices and exited to see two figures in the whiteout probing for crevasses below. We briefly chatted with the two Russians as they came by, asking about the whereabouts of camp 3 as they slowly postholed higher. Later that evening, we met Juho as he rapidly descended to camp 2, his summit bid over.Day 5After a string of increasingly alarming weather forecasts for the coming days, we decided to pack up and descend to camp 2. At least camp 2 was in a safe (we weren’t so convinced that our spot on the buttress was out of avalanche danger) and comfortable location. After a short descent to camp 2, we again were able to stretch out, dry our clothing and sleeping bags and enjoy the mountain a bit. But the forecast continued to deteriorate. Now, winds were expected to be 90 mph for a couple days, and the pattern after the major wind storm seemed unsettled, with a substantial snowfall forecasted afterwards. Did we have enough food to sit out the weather and still make a summit attempt? Even in the best of circumstances, we’d have no margin for extra days as our reserves of food and fuel would be depleted by a 4-5 day wait. After much deliberation, we settled on returning to base camp in the morning. And that’s when the fun began. I tore into scrambled eggs, sliced cheese, blueberry granola and pasta. No sense lugging extra weight back down the mountain. Plus, in the previous couple days we’d been purposefully starving ourselves to keep as much extra food as possible. In the evening, a huge serac ripped off the summit ridge and produced undoubtedly the largest avalanche I’ve witnessed. Though we were miles away and several thousand feet higher than where it landed, the powder blast steadily marched up valley and swept over us and into the Dikiy Glacier valley. We were now quite alone on the mountain, as only the Russian pair were above us. I rested well knowing our mission was clearer though we still needed to return through some tricky terrain to base camp.Day 6We woke up to another spectacular day. With our systems and teamwork now dialed, we packed up and roped up for the glacier below. The route was spectacular in early morning light and the firm snow made for enjoyable cramponing. Soon we reached the top of the fixed lines as a few climbers ascended on their own summit bids. The glorious weather and the presence of others pushing higher made us openly question our decision. We remarked that while we certainly didn’t want anyone to get into trouble, we almost wanted the weather to get nasty to justify our bailing in such perfect conditions. By noon I reached the comfort of base camp, now more of a deserted tent city. Relaxed and happy, my journey into the unknown was over.AftermathAs predicted, the storm rolled through. Winds first started to roll over the ridge, then things got nasty in base camp. People were holding the dining tent down for dear life. Some tents were blown away in base camp. Reports from the Russian duo, now in a snow hole at 6900 were of 135 kph winds and being pinned down.Pobeda: Route overview and considerations above our high point Camp 3 (5800m)Simple, but somewhat avalanche-prone slopes from Dikiy Pass. There was a huge snow cave there, which could be used to escape extreme weather. But in the Russian/Ukrainian exodus following their assault, this had essentially been turned into a field hospital. We let our minds run wild as there were reports of trash, blood, vomit and discarded dexamethasone needles.Camp 4 (6400m) Looked like fun and moderate climbing up the first rock band and in and out of couloirs to this airy perch. You know you’re getting close when you see the dead guy from last year. While somewhat sheltered, there’s space for just three tents. No snow cave option. Iranians were stuck here for six days. A tent collapsed here during our eventful night at 5600m.Camp 5 (6700 or 6900m)Sounded like there were snow cave options in either of these locations. West Pobeda (6900m) would be the only option for a one-day summit push that skipped the 7100m obelisk camp. Despite the simple climbing above 6400m, they both sounded like death traps. Go up there, get in a snow hole, and pray that the weather lets you get down.Summit Ridge This thing simply gets hammered with insane winds, usually out of the west. Every. Day. During my several week stay here, I observed just two days that would have been good to be up there. Let’s say an average day is 40-50 mile per hour winds (gusts can knock you over!). At 23,000 ft, air temperature in the vicinity of 0 °F. During the bad times the ridge is obscured by a giant cloud and snow plume. Winds were as high as 90 miles per hour (72 is a hurricane). On several occasions, we observed wind driven over a kilometer off the summit into western China.

Return of the Snow Leopard: The Film

Here's the short movie I filmed and edited as it happened. Enjoy!HariReturn of the Snow Leopard from Hari Mix on Vimeo.

Pobeda: Elusive and Unrepentant, Part 1

“It is better to return to Pobeda ten times than to not return once” –Gleb Sokolov

Fifty-nine mountains are higher. Plenty are steeper. But few are harder. Despite it’s relatively moderate climbing, Peak Pobeda routinely turns back—and kills—those who don’t take it seriously. Following several weeks of acclimatizing and strategizing, Pobeda casually thwarted our strong and competent team over a vertical mile below its summit. Here is the story:Day 0For days, base camp had been abuzz. Prior to potential summit windows, these places become infested with gossip, anxieties, impressive gear spreading, and endless conversations about the weather.Thirty or so Russians and Ukrainians, ascending in what can only be described as a military siege, were nearing the summit. Excitement was in the air, but with the short climbing season nearing its close, the rest of us sized up the others and scrambled to make arrangements. It was a veritable hodge-podge of mostly small teams.My own thinking and organization began to crystalize around a few core concepts: 1) Don’t do anything stupid, 2) I knew that despite my perfect health and strong climbing below 6000m, I had limited acclimatization. I was able to climb from base camp to Khan Tengri’s Camp 3 (5900m) in seven comfortable hours, but I only had one night there and two at 5600m. I needed a slower, more conventional ascent on Pobeda in order to acclimatize on the mountain. No sprinting to a snow cave at 6900m in just a couple days, 3) I needed the security of extra food, fuel, and strong shelter. This was shaping up to be the biggest pack I’d ever lugged…about two weeks of food and fuel. And my clothing system was outrageous—as warm as gear is made.All three factors drew me to joining an American couple living in Canada. Bob, a contractor and former Alaska Range guide, and Katherine, a philosophy professor with a calm, determined mind, had tons of big mountain experience, and I could tell that by partnering with experienced Americans, we had similar philosophies, risk tolerances (hell yes we were roping up on the lower glacier) and strategies for the summit. We got along well personally, which we knew would be vital for the inevitable tentbound storm days. We would try as hard as we could within our safety bounds. Team America was born.

Following several weeks of acclimatizing and strategizing, Pobeda casually thwarted our strong and competent team over a vertical mile below its summit. Here is the story:Day 0For days, base camp had been abuzz. Prior to potential summit windows, these places become infested with gossip, anxieties, impressive gear spreading, and endless conversations about the weather.Thirty or so Russians and Ukrainians, ascending in what can only be described as a military siege, were nearing the summit. Excitement was in the air, but with the short climbing season nearing its close, the rest of us sized up the others and scrambled to make arrangements. It was a veritable hodge-podge of mostly small teams.My own thinking and organization began to crystalize around a few core concepts: 1) Don’t do anything stupid, 2) I knew that despite my perfect health and strong climbing below 6000m, I had limited acclimatization. I was able to climb from base camp to Khan Tengri’s Camp 3 (5900m) in seven comfortable hours, but I only had one night there and two at 5600m. I needed a slower, more conventional ascent on Pobeda in order to acclimatize on the mountain. No sprinting to a snow cave at 6900m in just a couple days, 3) I needed the security of extra food, fuel, and strong shelter. This was shaping up to be the biggest pack I’d ever lugged…about two weeks of food and fuel. And my clothing system was outrageous—as warm as gear is made.All three factors drew me to joining an American couple living in Canada. Bob, a contractor and former Alaska Range guide, and Katherine, a philosophy professor with a calm, determined mind, had tons of big mountain experience, and I could tell that by partnering with experienced Americans, we had similar philosophies, risk tolerances (hell yes we were roping up on the lower glacier) and strategies for the summit. We got along well personally, which we knew would be vital for the inevitable tentbound storm days. We would try as hard as we could within our safety bounds. Team America was born. One hitch…we didn’t have the ideal shelter solution. I had a two man single-wall tent and they had a double wall, but essentially a one-man tent. We needed to distribute weight better: one tent, one stove. I set off on a multi-day and impressive, if I dare say so myself, diplomatic mission. Within a day, I brokered a straight up trade with a Dutch trio for our pie in the sky dream tent: a Mountain Hardwear Trango 3.1. Double wall. Strong as hell. And downright palatial. My single wall was perfect for their objective.____________________________________________________________________More writing coming as I get more juice. I am in base camp waiting out the storm. It is bad, even down here. Hopefully heli to Bishkek tomorrow!Hari

One hitch…we didn’t have the ideal shelter solution. I had a two man single-wall tent and they had a double wall, but essentially a one-man tent. We needed to distribute weight better: one tent, one stove. I set off on a multi-day and impressive, if I dare say so myself, diplomatic mission. Within a day, I brokered a straight up trade with a Dutch trio for our pie in the sky dream tent: a Mountain Hardwear Trango 3.1. Double wall. Strong as hell. And downright palatial. My single wall was perfect for their objective.____________________________________________________________________More writing coming as I get more juice. I am in base camp waiting out the storm. It is bad, even down here. Hopefully heli to Bishkek tomorrow!Hari

Contemplation and Commitment

A few nights ago I awoke at 2:00 to the jingle of my phone. Finding the willpower to extract myself from my sleeping bag is among my greatest challenges in the mountains, but I had no trouble getting dressed on this moonlight night. A sense of purpose filled me. The expedition has become simpler. Clearer.

A few nights ago I awoke at 2:00 to the jingle of my phone. Finding the willpower to extract myself from my sleeping bag is among my greatest challenges in the mountains, but I had no trouble getting dressed on this moonlight night. A sense of purpose filled me. The expedition has become simpler. Clearer.

The mission was unusual: retrieve my tent, stove, gas and a few other items from Camp 2 on Khan Tengri, return to base camp and recover as quickly as possible. After much deliberation, my focus has shifted entirely to Peak Pobeda, the colossal massif that presides over the Central Tien Shan.

The mission was unusual: retrieve my tent, stove, gas and a few other items from Camp 2 on Khan Tengri, return to base camp and recover as quickly as possible. After much deliberation, my focus has shifted entirely to Peak Pobeda, the colossal massif that presides over the Central Tien Shan. I shouldered a nearly empty pack: just a pair of light gloves, a couple layers, a liter of water and three small snacks. Soon I was hopping across the glacier, only breaking my crisp rhythm to hop the occasional crevasse. The crunch of the ice felt good under my feet. The limitless freedom of the high mountains buoyed my spirit. This is the type of climbing I love most. Completely unencumbered. Light. Fast. Just my breath and the mountain at night.Just above camp one, I reached my gear cache and swapped out my flimsy trail runners for clunky triple boots and crampons. As I donned my helmet and harness, a string of headlamps lit up the couloir above. One by one, I overtook the group. My rhythm intensified. Kick kick kick kick. I checked my watch. Over five hundred vertical meters per hour. This is how it feels to perform at my best. To be alive.As a whiteout closed in, I took a swig of water and kicked upward into Khan’s infamous bottleneck. No rest until camp two. I danced in and out of giant popcorn, some blocks the size of buses, from a monster avalanche a few hours earlier.I returned to base camp eight hours later, tired but content after the morning’s work. Now nothing other than waiting and targeting the right summit day remains. I believe in this team and our style. Paul is here, straight off Lenin Peak, where he spent four nights and five days in the solitary confinement of his tent at 20,000 ft in a blizzard. Juho, the Finnish phenom who turns twenty on Wednesday, is fresh off ascents of Lenin and Khan.Storms continue to batter the summit of Pobeda with ruthless intensity. Nearly three feet of snow blankets the upper elevations each day. Sustained winds are at least 30 miles per hour. Temperatures colder than minus forty are commonplace.The route involves a traverse of four miles of technical terrain, all over 23,000 ft. We require a summit day with less snow and wind. Now we settle into the rhythm of eating, resting, hiking, watching the sky and checking the forecast. The Ukrainians, Russians and Iranians have already begun their final push. We have spent countless hours discussing the forecast. We will know when the time is right.One thing I’ve learned in the big mountains: you must believe. And once you believe, you must commit. This is serious business. We will know when it is time to go. And we will not hesitate.I am strong. I am ready. I will try my hardest.Hari

I shouldered a nearly empty pack: just a pair of light gloves, a couple layers, a liter of water and three small snacks. Soon I was hopping across the glacier, only breaking my crisp rhythm to hop the occasional crevasse. The crunch of the ice felt good under my feet. The limitless freedom of the high mountains buoyed my spirit. This is the type of climbing I love most. Completely unencumbered. Light. Fast. Just my breath and the mountain at night.Just above camp one, I reached my gear cache and swapped out my flimsy trail runners for clunky triple boots and crampons. As I donned my helmet and harness, a string of headlamps lit up the couloir above. One by one, I overtook the group. My rhythm intensified. Kick kick kick kick. I checked my watch. Over five hundred vertical meters per hour. This is how it feels to perform at my best. To be alive.As a whiteout closed in, I took a swig of water and kicked upward into Khan’s infamous bottleneck. No rest until camp two. I danced in and out of giant popcorn, some blocks the size of buses, from a monster avalanche a few hours earlier.I returned to base camp eight hours later, tired but content after the morning’s work. Now nothing other than waiting and targeting the right summit day remains. I believe in this team and our style. Paul is here, straight off Lenin Peak, where he spent four nights and five days in the solitary confinement of his tent at 20,000 ft in a blizzard. Juho, the Finnish phenom who turns twenty on Wednesday, is fresh off ascents of Lenin and Khan.Storms continue to batter the summit of Pobeda with ruthless intensity. Nearly three feet of snow blankets the upper elevations each day. Sustained winds are at least 30 miles per hour. Temperatures colder than minus forty are commonplace.The route involves a traverse of four miles of technical terrain, all over 23,000 ft. We require a summit day with less snow and wind. Now we settle into the rhythm of eating, resting, hiking, watching the sky and checking the forecast. The Ukrainians, Russians and Iranians have already begun their final push. We have spent countless hours discussing the forecast. We will know when the time is right.One thing I’ve learned in the big mountains: you must believe. And once you believe, you must commit. This is serious business. We will know when it is time to go. And we will not hesitate.I am strong. I am ready. I will try my hardest.Hari

World of Ice

I am back in base camp after an excellent acclimatization rotation to ~19,500 ft on Khan Tengri. I should be prepared for a summit bid following the current storm. Major storms have been hitting over the last few days and likely won't subside until the weekend.Nuts and Bolts update:I am very healthy and happy here in base camp. People here on the South Inylchek Glacier are very friendly. A first for me in Central Asia…there are Americans here! How exotic! Also, a couple professors which is super cool. There are teams from Russia, Ukraine, Iran, Poland, Spain and other individuals from all over the world. This year is shaping up to be a festive one, as it is the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. Given the incomprehensible losses of the former Soviet Union during the war, it is a major objective here to commemorate this anniversary with an ascent of Peak Pobeda (Russian for Victory).I am very power and internet limited here, so for now I hope the following photo essay can tell part of the story.

Return of the Snow Leopard

Greetings from Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan! My five year love affair with the high mountains of Central Asia continues. This time, I return to the Tian Shan, the Celestial Mountains, to attempt Peak Pobeda. Known for some of the world's worst weather, Pobeda is certainly the crown jewel of the former USSR's five 7000m "Snow Leopard" peaks. I was hoping to write a more thought out piece but I have had too much to do in the mere 24 hours since my arrival. But I am in excellent physical, mental and emotional health, and I look forward to the journey ahead. I will have plenty of time ahead for reflection, writing, relaxation, and of course, good old fashioned suffering. It will be an adventure.Nuts and bolts: The Journey from HereIn two hours I depart for Karakol, near the banks of the great Issyk Kul. The next day we'll drive to At-Jailoo (jailoos are summer pastures) in the extreme northeast of Kyrgyzstan. The next day, early in the morning before the braided rivers swell with glacier runoff, I'll begin a six day trek up the Inylchek River and South Inylchek Glacier. Once there, I'll spend a few weeks climbing and acclimatizing on a few peaks including Khan Tengri (7010m) before attempting Peak Pobeda (7439m). More to come...I'm off to catch this jeep!How to (and how not to) follow alongI'll be out of good contact starting now. I will carry a SPOT messenger with me to post OK messages periodically, but I can't make guarantees about the frequency or quality of my communication until August 16 or so. I expect to check in within at least 8 days (my arrival at base camp) and weekly-ish after that. To track my progress, click the "Where's Hari??" link at the right of the header.Thank you to the American Alpine Club's Live Your Dream Grant and Osprey Packs for supporting this expedition!!!Take care,Hari

Greetings from Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan! My five year love affair with the high mountains of Central Asia continues. This time, I return to the Tian Shan, the Celestial Mountains, to attempt Peak Pobeda. Known for some of the world's worst weather, Pobeda is certainly the crown jewel of the former USSR's five 7000m "Snow Leopard" peaks. I was hoping to write a more thought out piece but I have had too much to do in the mere 24 hours since my arrival. But I am in excellent physical, mental and emotional health, and I look forward to the journey ahead. I will have plenty of time ahead for reflection, writing, relaxation, and of course, good old fashioned suffering. It will be an adventure.Nuts and bolts: The Journey from HereIn two hours I depart for Karakol, near the banks of the great Issyk Kul. The next day we'll drive to At-Jailoo (jailoos are summer pastures) in the extreme northeast of Kyrgyzstan. The next day, early in the morning before the braided rivers swell with glacier runoff, I'll begin a six day trek up the Inylchek River and South Inylchek Glacier. Once there, I'll spend a few weeks climbing and acclimatizing on a few peaks including Khan Tengri (7010m) before attempting Peak Pobeda (7439m). More to come...I'm off to catch this jeep!How to (and how not to) follow alongI'll be out of good contact starting now. I will carry a SPOT messenger with me to post OK messages periodically, but I can't make guarantees about the frequency or quality of my communication until August 16 or so. I expect to check in within at least 8 days (my arrival at base camp) and weekly-ish after that. To track my progress, click the "Where's Hari??" link at the right of the header.Thank you to the American Alpine Club's Live Your Dream Grant and Osprey Packs for supporting this expedition!!!Take care,Hari

A mini piggyback

I'm back to my usual summer pattern of getting into my research while simultaneously disappearing into the mountains for a while. This summer's travels started with a mini "piggyback" - a combo research and field adventure. This time, Sean and I headed to San Diego to give a talk and have some meetings at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scripps is filled with bright and energetic people who somehow manage to get work done despite their idyllic setting.

I'm back to my usual summer pattern of getting into my research while simultaneously disappearing into the mountains for a while. This summer's travels started with a mini "piggyback" - a combo research and field adventure. This time, Sean and I headed to San Diego to give a talk and have some meetings at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Scripps is filled with bright and energetic people who somehow manage to get work done despite their idyllic setting. After a few days of productive discussion, we headed north to the Eastern Sierra. Aiming for some alpine rock routes in the Whitney region, we shouldered packs with a few days of supplies and headed up the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek.

After a few days of productive discussion, we headed north to the Eastern Sierra. Aiming for some alpine rock routes in the Whitney region, we shouldered packs with a few days of supplies and headed up the North Fork of Lone Pine Creek.

Unfortunately, morning showers and even stronger afternoon thunderstorms prevented us from getting on any of the technical routes, but it was a great trip nonetheless.

Unfortunately, morning showers and even stronger afternoon thunderstorms prevented us from getting on any of the technical routes, but it was a great trip nonetheless.

Chasing Neutrons

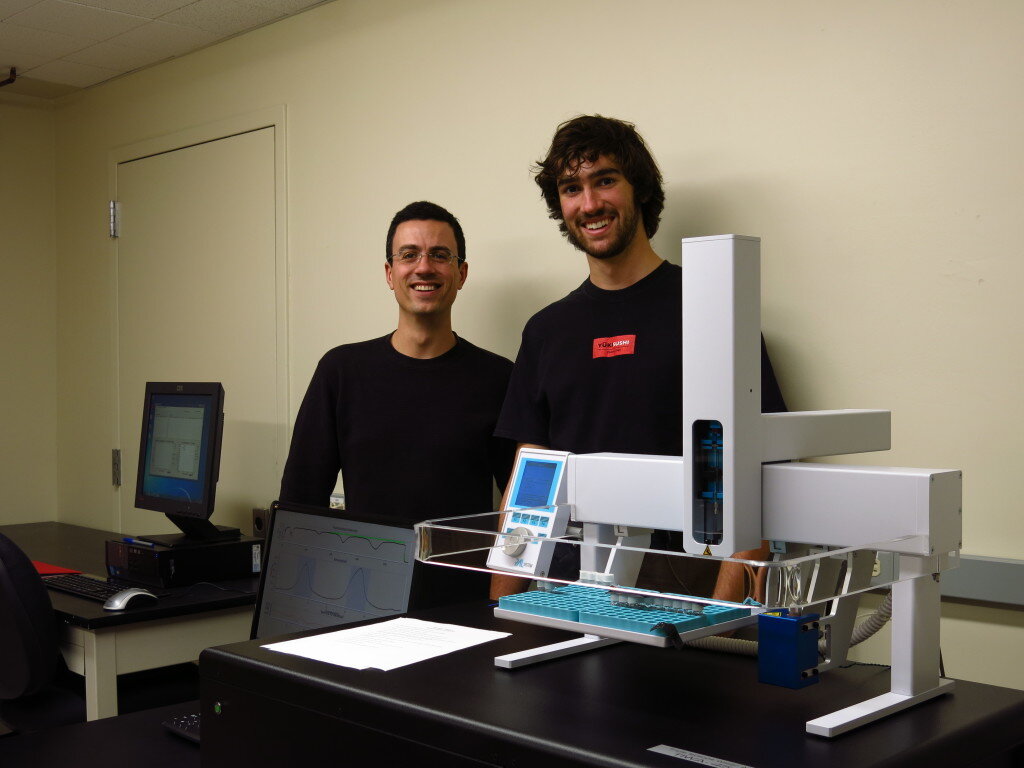

Ask any tenured or tenure-track professor about their first year and you're bound to get a seasoned, almost gleeful look in return. "Just wait a few years, it'll get easier," they'll say, as they recount the desperate sprint of starting out as a faculty member.A few months into my first year, I can officially report that faculty life presents a daunting set of challenges. And I've had it easy: no cross country move, no job search for a spouse, no young children to raise. But while the honeymoon years of infinite intellectual and recreational freedom that defined my graduate career have come and gone (hey, the pictures on this blog didn't take themselves!), I gaze out at the landscape of opportunities ahead.Lately, I've been coming to terms with the contrast between the countless problems I can work on and the startlingly short horizon defining the frontier of my knowledge and skills. Part of what's made the job so all-consuming have been the strategic questions, the big upfront decisions I make that will shape my research trajectory over the coming years. Not to mention figuring out how these "work" decisions will ultimately fit into a happy and fulfilling life. First step, many a scientist's rite of passage, building my own lab...

Ask any tenured or tenure-track professor about their first year and you're bound to get a seasoned, almost gleeful look in return. "Just wait a few years, it'll get easier," they'll say, as they recount the desperate sprint of starting out as a faculty member.A few months into my first year, I can officially report that faculty life presents a daunting set of challenges. And I've had it easy: no cross country move, no job search for a spouse, no young children to raise. But while the honeymoon years of infinite intellectual and recreational freedom that defined my graduate career have come and gone (hey, the pictures on this blog didn't take themselves!), I gaze out at the landscape of opportunities ahead.Lately, I've been coming to terms with the contrast between the countless problems I can work on and the startlingly short horizon defining the frontier of my knowledge and skills. Part of what's made the job so all-consuming have been the strategic questions, the big upfront decisions I make that will shape my research trajectory over the coming years. Not to mention figuring out how these "work" decisions will ultimately fit into a happy and fulfilling life. First step, many a scientist's rite of passage, building my own lab...

I'm also continuing to refine the "piggyback," where a work trip incorporates a bit of play. Case in point, spring break was spent with my student researcher Sean, who just happens to be a superb rock climber (wink). Read more of Sean's exploits here. So we dropped by Yosemite valley for a couple days on the way out to fieldwork in the Eastern Sierra near Reno. I gladly gave Sean all the runout pitches on valley classics including Snake Dike, the legendary line on Half Dome. Hiking out, I noticed a scratchy throat and proceeded to get violently sick for the rest of break and the next couple weeks, but all in all, it was a very successful trip sampling and otherwise.

I'm also continuing to refine the "piggyback," where a work trip incorporates a bit of play. Case in point, spring break was spent with my student researcher Sean, who just happens to be a superb rock climber (wink). Read more of Sean's exploits here. So we dropped by Yosemite valley for a couple days on the way out to fieldwork in the Eastern Sierra near Reno. I gladly gave Sean all the runout pitches on valley classics including Snake Dike, the legendary line on Half Dome. Hiking out, I noticed a scratchy throat and proceeded to get violently sick for the rest of break and the next couple weeks, but all in all, it was a very successful trip sampling and otherwise.

Oh, and I'll get back up in the big mountains too...I'm just shaking out before the crux!P.S. Thanks to everyone who's reached out to me with regards to the Nepal earthquake. Lots of friends over there have been affected, but luckily a lot of the news I'm getting from the ground now is better than I'd feared. Still many are in need. For those who've been asking, I've been recommending the American Himalayan Foundation as a great organization on the ground that's currently directing 100% of donations to relief and long term recovery in Nepal.P.P.S. A few years ago, I came across a couple mountain guides from Oregon who snapped these awesome shots of me in action on Bugaboo Spire in BC. Somehow my email address was temporarily lost, but look what came in the mail!

Oh, and I'll get back up in the big mountains too...I'm just shaking out before the crux!P.S. Thanks to everyone who's reached out to me with regards to the Nepal earthquake. Lots of friends over there have been affected, but luckily a lot of the news I'm getting from the ground now is better than I'd feared. Still many are in need. For those who've been asking, I've been recommending the American Himalayan Foundation as a great organization on the ground that's currently directing 100% of donations to relief and long term recovery in Nepal.P.P.S. A few years ago, I came across a couple mountain guides from Oregon who snapped these awesome shots of me in action on Bugaboo Spire in BC. Somehow my email address was temporarily lost, but look what came in the mail!

Big Will and the California Fourteeners

"Going to the mountains is going home" -John Muir

It's been too long. I joined the machine and got a "Real Job." I built my own lab this past fall (more on that later!). But the High Sierra are my home away from home. Last weekend I completed a seven year journey to climb each California's fifteen peaks over 14,000 ft...and each with a twist, be it a linkup, speed ascent, winter ascent or a non-standard route.

No peak was more challenging nor turned me back more than bulky Mount Williamson. It's not that Williamson is the most technical, nor the most mileage. It's just one of the bigger, more inaccessible piles of rubble you'll encounter. Williamson's routes are nearly Alaskan or Himalayan in proportion as they start from the Owens Valley floor, over 8,000 ft below the summit. They involve miles of up and down trail, thousands of feet of bushwhacking, scree, scrambling or rock climbing. For my fifth (or thereabouts) attempt on Williamson, I opted for the loose, brush-filled, icy boulder-hopping, snow climbing and scrambling sufferfest that is the North Fork of Bairs Creek. I don't know what's wrong with me but I eat this stuff up!

No peak was more challenging nor turned me back more than bulky Mount Williamson. It's not that Williamson is the most technical, nor the most mileage. It's just one of the bigger, more inaccessible piles of rubble you'll encounter. Williamson's routes are nearly Alaskan or Himalayan in proportion as they start from the Owens Valley floor, over 8,000 ft below the summit. They involve miles of up and down trail, thousands of feet of bushwhacking, scree, scrambling or rock climbing. For my fifth (or thereabouts) attempt on Williamson, I opted for the loose, brush-filled, icy boulder-hopping, snow climbing and scrambling sufferfest that is the North Fork of Bairs Creek. I don't know what's wrong with me but I eat this stuff up!

I got a super late start on Saturday because I-5 had been closed the day before due to an accident. I climbed the 1,500 or so feet to the "hard to find" notch, dropped down into the icy creek bed, and ascended thousands of feet of loose rock, willows and thorns to a decent bivy spot at ~9,600 ft. I felt quite good, hydrated well and had a nice dinner of noodle soup before turning in for the night. In the morning, I brewed up, hydrated and boulder hopped thousands of feet up to the crux of the route, a snowy couloir that provided excellent cramponing up to the 13,000 ft plateau beneath the summit slopes. A while later, I was on top, making the first winter ascent of the season and with the high sierra to myself. A fast and relatively uneventful descent (minus some inevitable thrashing) had me eating a nice dinner in town.

I got a super late start on Saturday because I-5 had been closed the day before due to an accident. I climbed the 1,500 or so feet to the "hard to find" notch, dropped down into the icy creek bed, and ascended thousands of feet of loose rock, willows and thorns to a decent bivy spot at ~9,600 ft. I felt quite good, hydrated well and had a nice dinner of noodle soup before turning in for the night. In the morning, I brewed up, hydrated and boulder hopped thousands of feet up to the crux of the route, a snowy couloir that provided excellent cramponing up to the 13,000 ft plateau beneath the summit slopes. A while later, I was on top, making the first winter ascent of the season and with the high sierra to myself. A fast and relatively uneventful descent (minus some inevitable thrashing) had me eating a nice dinner in town.

The Fourtneeners, a retrospectiveThanks to all with whom I shared these magnificent adventures...they wouldn't have been the same without you!! Here are some highlights from fourteener trips...Langley (with Mike) We went up this one dry Thanksgiving via a variation of Old Army Pass. The climbing wasn't the most memorable, but Mike ate a heroic amount of french fries in Lone Pine!

The Fourtneeners, a retrospectiveThanks to all with whom I shared these magnificent adventures...they wouldn't have been the same without you!! Here are some highlights from fourteener trips...Langley (with Mike) We went up this one dry Thanksgiving via a variation of Old Army Pass. The climbing wasn't the most memorable, but Mike ate a heroic amount of french fries in Lone Pine! Russell, Whitney, Muir (and Keeler Needle) (with John and Dave) What a blast. We went up the East Ridge of Russell...perhaps the finest 3rd class route I've ever been on (sorry Keyhole Route on Long's Peak). I threw in Keeler and Muir for good measure and then had a death march back to the Portal.

Russell, Whitney, Muir (and Keeler Needle) (with John and Dave) What a blast. We went up the East Ridge of Russell...perhaps the finest 3rd class route I've ever been on (sorry Keyhole Route on Long's Peak). I threw in Keeler and Muir for good measure and then had a death march back to the Portal.

Williamson Can't count the times I've said I was going to do this, but I made it up Shepherd's pass a couple times alone and with Warren, not to mention the honest effort on the Northeast Ridge with Brad

Williamson Can't count the times I've said I was going to do this, but I made it up Shepherd's pass a couple times alone and with Warren, not to mention the honest effort on the Northeast Ridge with Brad Tyndall One day winter ascent with Warren who also liked big days in winter.

Tyndall One day winter ascent with Warren who also liked big days in winter. Split Mountain Tried once before I soloed the St. Jean Couloir in winter. Wish I hadn't lost my camera after the ascent!

Split Mountain Tried once before I soloed the St. Jean Couloir in winter. Wish I hadn't lost my camera after the ascent! Middle Palisade I ran the stellar East Face route in 7:28 round trip, which I think due to some strange technicality may be the fastest known time. It's hard to imagine given how fast the 14er records are these days that this wouldn't be hours faster. Nonetheless, a fine day in the mountains on one of the nicest peaks in the high country. Brainerd and Finger Lakes are the gems they're talked up to be.

Middle Palisade I ran the stellar East Face route in 7:28 round trip, which I think due to some strange technicality may be the fastest known time. It's hard to imagine given how fast the 14er records are these days that this wouldn't be hours faster. Nonetheless, a fine day in the mountains on one of the nicest peaks in the high country. Brainerd and Finger Lakes are the gems they're talked up to be. Thunderbolt, Starlight, North Palisade, Polemonium Peak, Mount Sill (with Warren) The Palisades Traverse is still the longest day I've ever had in the mountains, a full 26 hours (2 sunrises in one day!!!). What a spectacular adventure. We didn't summit Sill, but I climbed the North Couloir after graduating undergrad only to break my arm tripping on the trail at First Lake (sorry Dad and Sue!)

Thunderbolt, Starlight, North Palisade, Polemonium Peak, Mount Sill (with Warren) The Palisades Traverse is still the longest day I've ever had in the mountains, a full 26 hours (2 sunrises in one day!!!). What a spectacular adventure. We didn't summit Sill, but I climbed the North Couloir after graduating undergrad only to break my arm tripping on the trail at First Lake (sorry Dad and Sue!)

White Mountain Peak Casually ran this in 2:58 car to car, also a fastest known time. Same as Middle Pal, I'd be shocked if some Yosemite hard man hasn't run this faster.Shasta (Tried a couple times, first with Leor, turned back due to insane winds) Finally got the weather right after my first expedition to Nepal in 2010. I soloed the Casaval Ridge in 27 hours...Stanford to Stanford. Just 11 hours on the route proper. One of my finest days ever in the mountains. Sunrise from the Catwalk was among the best I've ever seen.

White Mountain Peak Casually ran this in 2:58 car to car, also a fastest known time. Same as Middle Pal, I'd be shocked if some Yosemite hard man hasn't run this faster.Shasta (Tried a couple times, first with Leor, turned back due to insane winds) Finally got the weather right after my first expedition to Nepal in 2010. I soloed the Casaval Ridge in 27 hours...Stanford to Stanford. Just 11 hours on the route proper. One of my finest days ever in the mountains. Sunrise from the Catwalk was among the best I've ever seen.

What can clay tell us about the past?

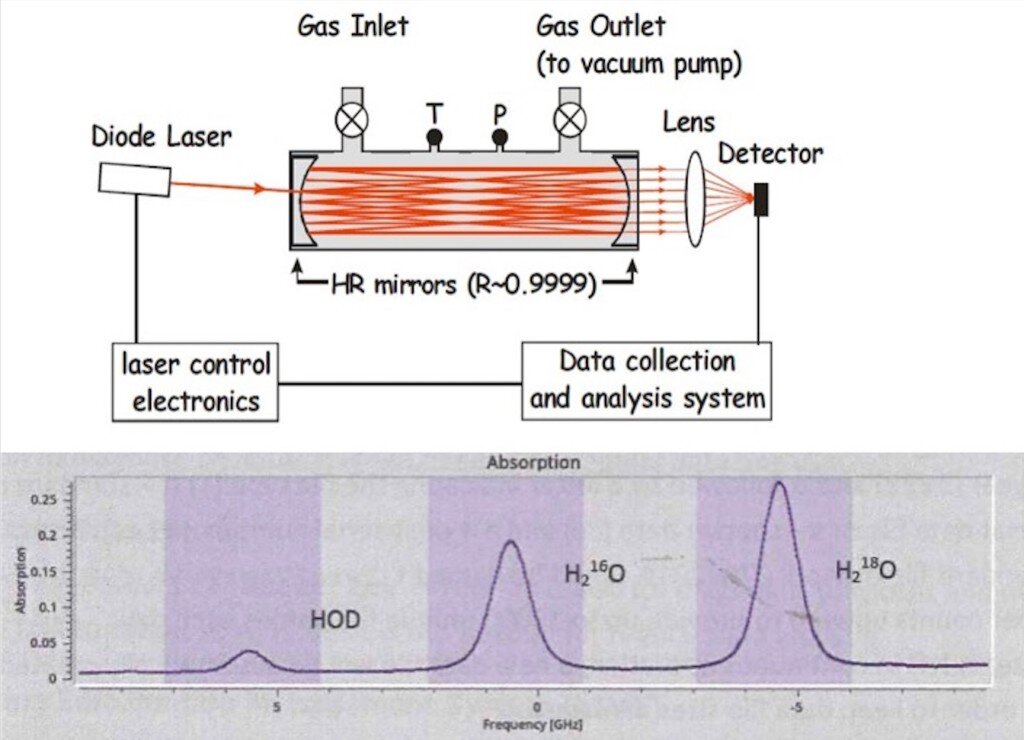

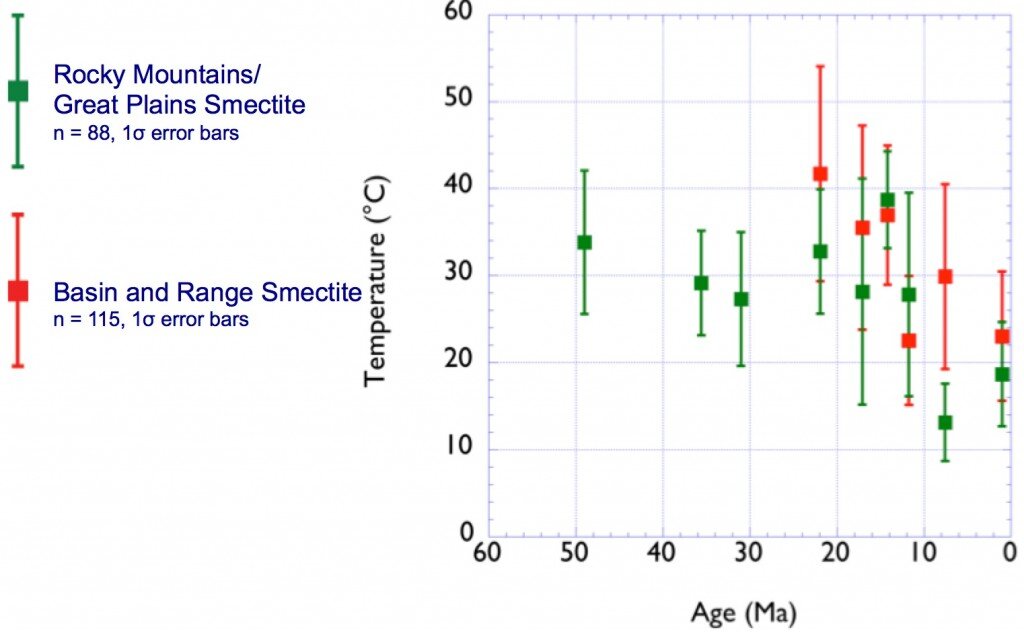

How hot was it in Colorado yesterday? Ok, how about 20 million years ago? Hmm, that one seems trickier to answer. I recently took a stab at this and other questions in North American paleoclimate in the final chapter of my PhD, which has been accepted in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, a leading geochemistry journal. I've been somewhat reluctant to write about this as it's not exactly the most accessible work I've done, plus I've been trying to run away from the last remaining scraps of my PhD in search of fresh research topics!Anyhow, here's a go at some of what I've been working on since 2008. Telling the conditions in the geologic past has always been challenging, but our foundation of knowledge has always been observational science. For many decades, paleontologists have studied fossils to determine information about ancient climate and environments. One metric involves analyzing the shapes of leaves, then using statistical models to determine things such as ancient temperature and rainfall. I belong to a community of scientists who use the chemistry of ancient sediments to learn about the past. Harold Urey's discovery of deuterium (hydrogen with an extra neutron) not only won him the Nobel Prize in 1934, but also gave birth to an entire field of stable isotope paleoclimatology. As it turns out, many natural processes preferentially take one isotope (forms of an element with different masses) over another in what is known as isotopic fractionation. For example, photosynthesis preferentially uses "light" carbon-12 in CO₂ over the heavier carbon-13. One of the best things from a climate standpoint, though, is that most isotopic fractionation is temperature dependent, meaning that we can calculate temperature if we know some more things about the system. Most famously, our best records of climate change over geologic timescales come from ancient fossils of tiny foraminifera buried in ocean sediments. The chemistry of their shells, made out of calcium carbonate, tells us about the temperature and amount of ice on the ancient earth.Here's where the clay comes in...clay minerals form as weathering products in soils. The clay forms in equilibrium with ancient water, and preserves the ancient isotopic signatures of oxygen and hydrogen, allowing us to study the ancient climate. I've been using the peculiar chemistry of smectite, a particular type of clay that weathered out of volcanic ash from enormous eruptions to tell the temperature history of western North America.

I belong to a community of scientists who use the chemistry of ancient sediments to learn about the past. Harold Urey's discovery of deuterium (hydrogen with an extra neutron) not only won him the Nobel Prize in 1934, but also gave birth to an entire field of stable isotope paleoclimatology. As it turns out, many natural processes preferentially take one isotope (forms of an element with different masses) over another in what is known as isotopic fractionation. For example, photosynthesis preferentially uses "light" carbon-12 in CO₂ over the heavier carbon-13. One of the best things from a climate standpoint, though, is that most isotopic fractionation is temperature dependent, meaning that we can calculate temperature if we know some more things about the system. Most famously, our best records of climate change over geologic timescales come from ancient fossils of tiny foraminifera buried in ocean sediments. The chemistry of their shells, made out of calcium carbonate, tells us about the temperature and amount of ice on the ancient earth.Here's where the clay comes in...clay minerals form as weathering products in soils. The clay forms in equilibrium with ancient water, and preserves the ancient isotopic signatures of oxygen and hydrogen, allowing us to study the ancient climate. I've been using the peculiar chemistry of smectite, a particular type of clay that weathered out of volcanic ash from enormous eruptions to tell the temperature history of western North America. My study involved collected hundreds of samples of weathered ash from all over western North America, with ages ranging from 620,000 years to about 30 million years. I separated the clay minerals using a centrifuge (read: lots of dishwashing!) and analyzed the oxygen and hydrogen isotope composition using mass spectrometry.

My study involved collected hundreds of samples of weathered ash from all over western North America, with ages ranging from 620,000 years to about 30 million years. I separated the clay minerals using a centrifuge (read: lots of dishwashing!) and analyzed the oxygen and hydrogen isotope composition using mass spectrometry. What do our results say? Well, quite a few things, but temperatures in North America follow global prevailing trends. It was quite a lot warmer (~10-15 degrees C) around 15 million years ago at a time known as the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was the most recent time of elevated global temperatures similar to where we may be headed by 2100 with modern climate change. If my results are any indication, continental interiors may warm to a greater degree than global averages.

What do our results say? Well, quite a few things, but temperatures in North America follow global prevailing trends. It was quite a lot warmer (~10-15 degrees C) around 15 million years ago at a time known as the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was the most recent time of elevated global temperatures similar to where we may be headed by 2100 with modern climate change. If my results are any indication, continental interiors may warm to a greater degree than global averages.

Black Kaweah: Earning an adventure

The wild Kaweahs of the southern Sierra Nevada have long been on my mind. Their reputation for remoteness, lightning strikes, loose rock make even approaching these peaks a challenging and rewarding experience. Jonathan and I set off from the Bay Area for Sequoia National Park's Mineral King late in the evening to miss traffic. By the time we got to the trailhead, it was 2:30 AM and we were delirious. I did my standard bivouac on top of a picnic table, slept like a rock and woke up at 7 to get packing. Fortunately, Jonathan and I were on the same page with our gear...no tent, trail running shoes, and 3oz windbreakers would be our weapons of choice. Offsetting the lightweight clothing, we opted to take a ton of food and a full climbing rope and rack for an shot at the seldom-attempted Kaweah traverse, a notoriously heinous, loose climbing objective. After a long talking to by the rangers, we set off cross country over two high ranges, crossing Glacier Pass and Hands and Knees Pass before dropping down to our bivy spot on Big Arroyo.

The wild Kaweahs of the southern Sierra Nevada have long been on my mind. Their reputation for remoteness, lightning strikes, loose rock make even approaching these peaks a challenging and rewarding experience. Jonathan and I set off from the Bay Area for Sequoia National Park's Mineral King late in the evening to miss traffic. By the time we got to the trailhead, it was 2:30 AM and we were delirious. I did my standard bivouac on top of a picnic table, slept like a rock and woke up at 7 to get packing. Fortunately, Jonathan and I were on the same page with our gear...no tent, trail running shoes, and 3oz windbreakers would be our weapons of choice. Offsetting the lightweight clothing, we opted to take a ton of food and a full climbing rope and rack for an shot at the seldom-attempted Kaweah traverse, a notoriously heinous, loose climbing objective. After a long talking to by the rangers, we set off cross country over two high ranges, crossing Glacier Pass and Hands and Knees Pass before dropping down to our bivy spot on Big Arroyo.